Eva Buto

Managing Editor

This post was originally published on October 1.

When the Internet started, it was a way to contact friends or share information over text-based forums, as well as browse cat videos. Over the years, the Internet has become less saturated with personal connection. Influencers are often covertly pushing products under the guise of connecting with their audience, while filters and Photoshop remain consistently used in almost every image. All of this has been well-known. But in the past few years, using artificial intelligence to create content has become more popular. AI that creates content based on prompts is known as generative AI. Popular examples include Google’s Gemini AI, image generator Midjourney, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and China-based competitor Deepseek.

Now, most text-based generative AIs are Large Language Models, or LLMs. ChatGPT, Deepseek, and Gemini all fall into this category. A lot of time, energy, and natural resources are invested in the creation and cultivation of these AIs. These AIs are first given huge amounts of data sets to consume. These sets are then fine-tuned, making sure that the AI is being provided good data. Though, in larger models, it is still relatively common for false information to slip through.

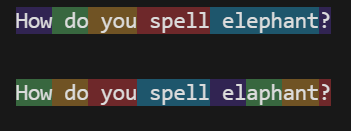

Then, it comes time to test and then use the AI model. First, it is given a prompt: let’s say it is asked the color of the sky. The first thing the AI does is break the prompt down into small, numerical pieces called “tokens”, in a process called tokenization. OpenAI themselves have an open processor on Platform AI so users can see how tokens are being converted in real time. Common words are often grouped together, with OpenAI stating their model often converts four letters on average: about 0.75 of a word. I used PlatformAI to generate the following example:

The sentence was broken into tokens which are smaller parts of the whole that help the AI understand what is being input. The misspelling causes an interesting interaction: the AI now breaks it into more chunks. Instead of converting the word into a string of numbers corresponding with ‘elephant,’ it needs to parse through each section of the word, almost as if sounding it out.

LLMs run on logarithmic output: it strings together a reply by looking at its sources and deciding what word is likely to come next. Most models, such as ChatGPT, have a preset of how much variation they allow which is very low. Answers can vary in size and content, but simple questions often lead to very similar answers. Ask it what two plus two is, and you will likely get an answer such as “2+2=4” or “two plus two is equal to four.” The tokens input lead to similarly grouped token outputs: these similar symbols and words, such as addition and integers, are easily found together in many different sources. Users cannot control the variation in models such as ChatGPT.

This is also how mistakes in ChatGPT and other LLMs can arise. For example, you are given a difficult problem in a Chemistry class, so you ask ChatGPT to answer it for you. While this is not outright prohibited by Penn State University, is not encouraged by many professors and may be considered a violation of academic integrity. You ask it your question, and it checks all of the sources such as Chegg or Mathway for you. It’s important to note that it is not actually calculating anything for you. It’s drawing upon multiple sources and making a composite answer.

This works under two circumstances: your professor’s question was once answered online, and people answered it correctly. The earlier grammatical mistake illustrates how AI can go wrong: it pushes the most likely answer it finds online, and takes the incorrect tokens to string them back into the ‘correct’ answer. Now, imagine this, but with your professor changing one integer in a multi-step chemistry problem. Or, a similar problem currently being posted online, that would be broken down into similar tokens. Now, these are processed and used to generate an answer: the incorrect one, based on the tokens the AI was trained on.

Whether or not people agree that AI belongs in the academic world, it is undeniably present. Professors are attempting to incorporate it into their classes to see where AI fits into their field. Students have taken to it to answer problems quickly. Regardless of moral stance on AI, if one is going to use a tool, it is good to understand how the tool works. AI has many strengths, such as handling large amounts of data and giving the composite answer to questions found on the Internet. But for calculating and understanding homework problems, it is important to understand the fallacies a student may encounter.

Leave a comment